SURVEY: ILLEGAL DRUGS

Better ways

Jul 26th 2001

From The Economist print edition

If enforcement doesn't work, what are the alternatives?

IMPRISONMENT is unlikely to clinch the war against drugs. What

other weapons are there? Education for the young is one

possibility, although its record is discouraging: one recent report

complains that “large amounts of public funds...continue to be

allocated to prevention activities whose effectiveness is unknown

or known to be limited.” However, for habitual users, the

alternatives are more promising. Drug reformers advocate projects

collectively known as “harm reduction”: methadone programmes,

needle-exchange centres, prescription heroin.

One of the most

remarkable projects

designed to reduce harm

is going on in a clinic two

floors up in a side street

in Bern, in Switzerland.

The clinic is tidy: no

sign, apart from covered

bins full of spent

syringes, of the 160

patients who come two

or three times a day to

receive and use

pharmaceutical heroin.

This Swiss project grew

out of desperation: an

experiment in the late

1980s to allow heroin use

in designated sites in

public parks went badly

wrong. Bern had its own

disagreeable version of

Zurich's more notorious

heroin mecca, Platzspitz.

In 1994 the city

authorities in Zurich and

Bern opened “heroin maintenance” clinics, of which Bern's KODA

clinic is one.

It takes addicts from the bottom of the heap. By law, patients

must not only be local residents: they must be the addicts with

the greatest problems. Christoph Buerki, the young doctor in

charge, describes the typical patient as a 33-year-old man who

has been on heroin for 13 years and made ten previous efforts to

stop. Half his patients have been in psychiatric hospitals, nearly

half have attempted suicide, many suffer from severe depression.

Given such difficult raw material, the clinic has been remarkably

successful.

First of all, relatively few drop out of the programme, in contrast

to most other drug-treatment schemes. After a year, 76% are still

taking part; after 18 months, 69%. Of those who drop out,

two-thirds move on either to methadone, a widely used heroin

substitute, or to abstinence. Two-thirds of the patients, stabilised

on a regular daily heroin dose, find a job either in the open market

or in state-subsidised schemes. Crime has dropped sharply. “To

organise SFr100-200 ($57-113) a day of heroin, you need either

prostitution or crime, especially drug-dealing,” says Dr Buerki. Yet

a study that checked local police registers for mentions of

patients' names found a fall of 60% in contacts with the police

after the addicts started coming to the clinic. Hardly any patients

attempt suicide or contract HIV, because the clinic sees them

daily, monitors their physical and psychological health, and

administers other medicines when they come in for their heroin.

Interestingly, one side benefit of the programme seems to be to

reduce the use of cocaine. Dr Buerki dislikes the idea of prescribing

that drug because of its unpredictable effects. The vast majority

of his patients are taking it when they first arrive, 56%

occasionally and 29% daily. After 18 months of treatment, 41%

have stopped using cocaine and 52% use it only occasionally.

Given that there is no equivalent of methadone to wean cocaine

users off their drug, that is a hopeful finding.

Switzerland's experience, says Robert

Haemmig, medical director of Bern's

Integrated Drug Services Programme,

suggests that abstinence may not be the

right goal for heroin addicts. People can

tolerate regular doses of heroin for long

periods, but if they give up for a period

and then start again they run a big risk of overdosing. “It's always

hard to tell politicians that abstinence is quite a risky thing for

these people,” he says.

Heroin maintenance is still used sparingly in Switzerland, for about

1,000 of the country's estimated 33,000 heroin addicts. Most of

those in treatment get not heroin but methadone. But the

programme's success suggests that there are ways to help even

the most “chaotic” drug users, if governments are willing to be

open-minded. Predictably, the Swiss doubt whether it would work

everywhere: “You need a society with well-paid professionals and

a low rate of corruption in the medical profession,” says Thomas

Zeltner, the senior official in the federal health ministry. But the

economics of the programme are impressive. It costs much the

same as methadone maintenance, and considerably less than a

therapeutic community or in-patient detoxification. It reaches

patients that no other programme can retain. It reduces crime and

legal costs and saves much spending on psychiatric hospitals.

Market separation

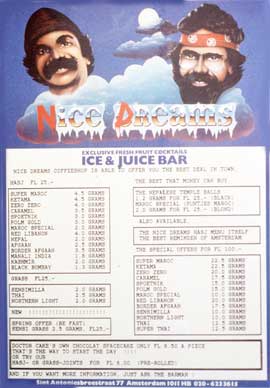

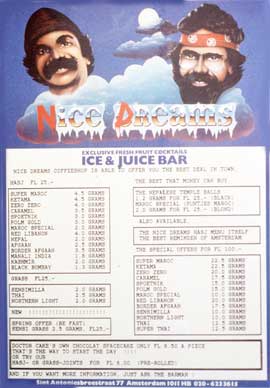

The Swiss heroin maintenance programme shows what can be

achieved when a country starts to think of drug addiction as a

public-health problem rather than merely a crime. The Netherlands

has taken a similarly pragmatic approach to marijuana for the past

quarter of a century. It has aimed to separate the markets for

illegal drugs to keep users of “soft” ones away from dealers in the

harder versions, and to avoid marginalising drug users. “We have

hardly a single youngster who has a criminal record just because

of drug offences,” says Mr Keizer, the Dutch health ministry's

drug-policy adviser. “The prevention of marginalisation is the most

important aspect of our policy.”

The Dutch Ministry of Health helps to finance a project by the

independent Trimbos Institute of mental health and addiction, to

test about 2,500-3,000 ecstasy tablets a year for their users.

“When we find substances such as strychnine in the tablets, we

issue a public warning,” says Inge Spruit, head of the institute's

department of monitoring and epidemiology.

What makes this approach work is the Dutch principle of

expediency, which has already proved useful in dealing with other

morally contentious issues such as abortion and euthanasia. The

activity remains illegal, but under certain conditions the public

prosecutor undertakes not to act. Amsterdam's famous coffee

shops, with their haze of fragrant smoke, are tolerated provided

they sell no hard drugs, do not sell to under-18s, create no public

nuisance, have no more than 500 grams (18 ounces) of cannabis

on the premises and sell no more than 5 grams at a time.

Erik Bortsman, who runs De Dampkring, one of Amsterdam's largest

coffee shops, grumbles that the police (and, worse, the taxmen)

raid him two or three times a year, weighing the stock, checking

the accounts and examining employees' job contracts. Sounding

like any other manager of a highly regulated business, he

complains that ordinary cafés that stock cocaine behind the

counter get by with no restraints. He points out, too, that it does

not make sense to allow youngsters to buy tobacco and alcohol at

16 but stop them from buying cannabis until they are 18.

But his main grouse is that, although Dutch police allow the

possession of small amounts of drugs for personal use, he is

forbidden to stock more than 500 grams, and his purchases remain

technically illegal. This contradiction is at the heart of Dutch drugs

policy. Ed Leuw, a researcher from the Dutch Ministry of Justice,

believes that a majority of Dutch members of parliament would like

to legalise the whole cannabis trade. Why don't they? Partly

because it would further increase the hordes of tourists from

Germany, Belgium and France that come to take advantage of the

relaxed Dutch approach; but mainly because the Dutch have

signed the United Nations convention of 1988, which prevents

them from legalising the possession of and trade in cannabis.

However, Switzerland may have found a way around that

obstacle. In a measure that must still pass through parliament, the

government proposes allowing the growing of, trade in and

purchase of marijuana, on condition that it is sold only to Swiss

citizens and that every scrap is accounted for. All these activities

would remain technically illegal, but with formal exemption from

prosecution, in line with Dutch practice. There is no precedent for

this in federal Swiss law. “We wouldn't have done things this way

if we hadn't signed the UN convention,” admits Dr Zeltner.

Extending the model

Could Dutch and Swiss pragmatism be the basis of wiser policies

across the Atlantic? Among lobbyists, the idea that the aim of

policy should be to reduce harm is extremely popular. At the start

of June, the Lindesmith Centre, newly merged with the Drug Policy

Foundation, another campaigning group, held a conference in

Albuquerque, New Mexico, where speaker after speaker argued

that current American policies did more harm than good.

A brave minority of politicians agrees, including Gary Johnson, New

Mexico's Republican governor. He is aghast at the lopsided severity

of drugs laws. “Our goals should be the reduction of death,

disease and crime,” he says, claiming that many other governors

share his views.

For the moment, Mr Johnson is seen as a maverick. “The

harm-reduction approach doesn't sell well in the United States,”

says John Carnevale, formerly of the Office of National Drug

Control Policy. What is forcing more debate, he reckons, is a

movement among the states to allow the medical use of marijuana,

and perhaps the perceived injustice of imprisoning so many young

black men.

The campaign to allow the use of marijuana for medical treatment

recently received a setback with a ruling by the Supreme Court

against the cannabis buyers' co-operatives that have flourished

mainly in California. But public opinion seems to be cautiously on

board: a 1999 Gallup poll found 73% of Americans in favour of

“making marijuana legally available for doctors to prescribe in order

to reduce pain and suffering.”

Change, if it comes, will start at state level. But it will come

slowly. Governments everywhere find it hard to liberalise their

approach to drugs, and not just because of the UN convention:

any politician who advocates more liberal drugs laws risks being

caricatured as favouring drug-taking. Still, the same dilemma once

held for loosening curbs on divorce, abortion and homosexuality,

on all of which the law and public opinion have shifted.

Public opinion is clearly shifting on drugs, too. When the Runciman

Report in Britain last year advocated a modest relaxation of the

laws on marijuana, the Labour government raced to condemn it. It

hastily changed its tune when most newspapers praised the

report. And it is worth recalling that at the time of America's 1928

election, Prohibition enjoyed solid support; four years later the

mood had swung to overwhelming rejection.